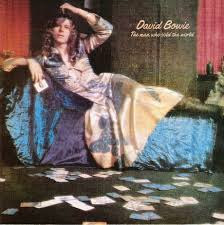

David Bowie

The Man Who Sold The World (1970) REVIEW

David

Bowie is a man that has quite carefully made himself a difficult man to

describe. On this album he makes no attempt to stray away from the poetic

powers he possesses as he crafts a variety of narrators and angles of a world

that he himself creates. The album, while utilizing the anonymity of the

outlandish simultaneously conveys a world view defined by paranoia and fear of

the unknown. It is almost unspeakably brilliant (but I’m going to speak about

it anyway.)

I

would describe to you the unit that is this band, comprised of: Mick Ronson

(guitar, and vocals), Mick Woodmansey (drums, and percussion), Tony Visconti

(electric bass, piano, and guitar), Ralph Mace (moog synthesiser) and David

Bowie (vocals, guitar, and stylophone) if the power of my measly words could

somehow provide any depth of what they were capable of together. Instead I ask

that you find a keen description (albeit the polar opposite of concise) of

their musicianship in each of the track’s descriptions.

The

album opens with “The Width of a Circle:” a sombre and jazzy twang song that

jolts awake the listener who is yet unsuspecting of the power of this album:

the rebirth that occurs on each song without fail. The song offers raw vocals

with heart-felt plummeting vowels that combat the “simple black bird” the

narrator mentions, immune to the complexities of its surroundings “happy as can

be.” Bowie’s lyrics initiate a taunting vibe that resurfaces throughout the

record: he recites inside jokes that refuse to remain merely passive poetry.

Bowie succeeds in establishing a surreal sorrow that is only the ominous

beginning to an album chock full of desperately communicative tragedy and

crooked humour. One could consider the drums punctuation to the undulation of

the narrator’s mania – stirred about by the guitar and instrumental

composition. The narrator claims that “God took his logic for a ride” but the

listener knows for a fact that Bowie is already exercising his immeasurable

instrumental genius. The lyrics are delightfully wicked, tainting with a

devilish finger the inanimate in an atmosphere purgatorial and pierced with a

cryptic pain.

“All

The Madmen” is a quintessential track in the history of David Bowie. It bravely

complements the dry works on mental illness such as schizophrenia. The song

strives to slow down the chaos of the illness Bowie’s brother had suffered

with. Each line managing to be a resounding poetry that attempts to cure his

aching soul rather than to broadly confront a topic often presented through

facts rather than the emotions of the afflicted. The music belongs in a tragic

circus: as metal crashes against metal, it becomes a mess of musical crudeness

that bolsters the lyrical complexity that lingers fearlessly. The speaker is

strangely aware of his circumstances in a stinging contentedness (“all the

madmen are all as sane as me.”) The song is impossibility: a construction of

nonsense assembled to help the listener learn of a situation which muddles the

definition of saneness. It is empathetic with harsh backing music that conveys

the horror and foreboding of a suspenseful and suffocating world faced by those

who are trapped in the confines of mental illness.

“Black

Country Rock” is a significant lift in the record. The guitar and steady jangly

drums play along with Bowie’s lyrics discussing a “crazy view.” It is memorable

for its energetic musical spurts and rather static visual imagery. The song is

a lesson in vagueness, in the “less is more” philosophy that Bowie uses to

trigger intrigue into his lyrics and a willing purchase from listeners into his

reliably catchy tunes with the bluesy twang he wields so well.

“After

All” introduces itself with a romantic but resistant Latin-guitar rhythm. It

teases the listener with spare descriptions of figures who blur into a

misshapen mass: locked together by their basic humanity and separated by a

difference in ability or age. With a use of brass instruments as a respectfully

sad tone it provides a view of being disowned that lulls the listener into a

submissive acceptance of a negative force. The predominant voice belongs (very

cleverly) to the backing vocalists who personify the oppressed (I viewed it as

a rally song for the people who suffer from forces such as a dictator in a

fictional world filled with pain.) At first listen, one might think the song is

about a vision quest: “we’re painting our faces and dressing our thoughts from

the skies” brings to mind flighty, almost forgettable flits of joy. But the

song makes itself so much more. The narrator describes the little influence he

has in the grand scheme of the world, and his non-belonging: “we’re nobody’s

children at all.” Bowie butts heads with the narrator by creating lyrics that

stick to your ribs (that hold a lot of weight): mainly the surprisingly sad “oh

by jingo.” The song is an unresolved resolution, a foreboding. It turns a

tragic sphere sideways as it tapers off before an unsuspicious calmness can be

enveloped by the zealous gloom of the song’s entirety. It keeps you on your

toes, as it discusses a march to apocalypse.

“Running

Gun Blues” is an immediately spooky track that clasps thundering tambourine

(mimicking a frantic pulse) as Bowie sings in a child’s voice about death. The

narrator “promotes oblivion” as he unabashedly tackles the topic of brutal

warfare. He describes an addiction to a shameless, power-inducing feeling that

comes with taking the lives of others, of taking your future into one’s own

hands. Bowie’s feelings on war are irrelevant as the songs delves deep into the

fire and passion that belongs with the narrator and the sense of belonging

missing in “After All” and a sense of sadness that pervades the record.

“Saviour

Machine” places a conspiratorial lens on a grand scale operation and plan

devised by a cruel and manipulative government. It drops ideas of plagues and

bombs on the unsuspecting masses that live in the song (and in the face of

oblivion) and on the other side of the stereo which blares Bowie’s glorious

words of a world submerged in a catastrophic inter-dimensional depression. The

song is a fantasy that stretches reality while punching it into a mould of

tangibility to set off urgency in the listener. It is dooming: the guitar rails

on relentlessly with unyielding drums to shape the prophecy of paranoia. Bowie

has now revealed himself as startlingly able to create an entire world (which

at first mention is innocuously bizarre, and later revealed to be on the

precipice of destruction) in the span of a concise four minutes. Not only are

the crimes he croons about alarming, the talent behind his tales is

unflinchingly present.

“She

Shook Me Cold” brings to mind visions of the merciless yet undeniably womanly

Lady Macbeth. The music is bass-fueled as it glides under Bowie’s words

effortlessly, bringing to life a stark vision of a woman constructed entirely

of impossibility: of awareness, and realistic perception (that Bowie, the

effortless artist, ironically exaggerates.)It is a smart, multi-dimensional

character profile that refuses the listener any subtlety or ignorance of the

mysterious woman’s abilities.

“The

Man Who Sold The World” is a musically hypnotic relief to the album. It is

interesting to hear it amongst the caliber of the album’s other tracks rather

than out on its own in a world of briefly described singles. The listener

recognizes that it belongs in the atmosphere Bowie has provided on the album.

It is lyrically calm and contemplative compared to the other heart-stopping

tracks on the album but is nonetheless unsettling. The song provides what some

of the others refuse: the feeling of unflinching and imminent doom is slowly

released with the intricacies and beauty the song radiates. The song reveals

Bowie as human because it proves that he can ask questions in addition to

stirring up a plethora of unanswerable ones in the other tracks. It discusses a

mysterious man, a mysterious fate but answers a question in humanity and

dysfunctional reality (the only kind that can be found in the warping and

perception-shifting album.) The song is enigmatic and far from dull but it is

(for me, at least) a reminder of the world that the listener has lost touch

with in the seven songs before this one. The album in its equally avant-garde

surroundings becomes a jagged puzzle piece rammed so as to complete not

coherent puzzles, but a non-linear psyche. This psyche has been artistically

perturbed to an excessively brilliant degree by a songwriter and a band with intense

insight and musical prowess.

“The Supermen” opens with echoes that bounce

off cave walls with backing vocals that follow suit. It describes the horrid

fates of a mysterious group of men. It beautifully concludes the fleeting

fantasy Bowie has described so completely and yet so sparingly. One which

intertwines humanity with the alien: insensitive celebrations, the death of

gods and the innocent, the march of the apocalypse, the evil and the madness of

men. It puts a face on the suffering Bowie has predicted, has prescribed and

described so uniquely in each track before it. It personifies a pain that was

at first voiced cold, with roots in psychological analysis character work, the

narrators of which had mercy that was simply invisible. The song mentions the

“Supermen’s” “solemn, perverse serenity” and I am unable to come up with a

better description for the album itself.

I’m

sure if you were to ask David Bowie himself, the remarkable complexities that

he has exorcised within the confines of this album would continue to surprise

him – there are a number of subconscious surprises in addition to a variety of

staining messages at the forefront. The album is laced generously with the

enigma of witchcraft (a worldly fascination) and the hallucinogenic qualities

that inhabit the freakiest of fantasies, but as this album shows, emanate from

somewhere much more real – from the depths of confused souls, from a hurt

heart, from a studious scholar’s brain. I know this album has sparked many a

fan’s fandom, and many a songwriter’s creeping envy. For good reason.

-K. MacFarlane

I remember this review! I absolutely love your take on this album! One of my favorite Bowie Albums for sure, and one of my favorite albums of all time! Your review is as beautifully and introspectively written as the album is itself. Definitely complements the atmosphere of the album. I'm sure many music nerds who read this review will be like "Yessss!" and music nerds who have never heard this album would definitely be intrigued upon reading this. I also agree with you that after hearing the titular track along with the rest of the album, I definitely saw it in a new light along with the foreboding themes and sounds of the record. If anything, I thought it was a much lighter track musically and melodically than the rest of the album. Idk about you, but I have noticed certain musical influences on this album, such as "Running Gun Blues", which reminded me of something The Who would write, melodically and thematically, and "She Shook me Cold" reminded me a little bit of Led Zeppelin, with the vocals mimicking the guitar riff. Overall, incredible review!!!!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for your kind words! I'll have to look more into the Zeppelin parallels (haven't listened to much.)

ReplyDelete